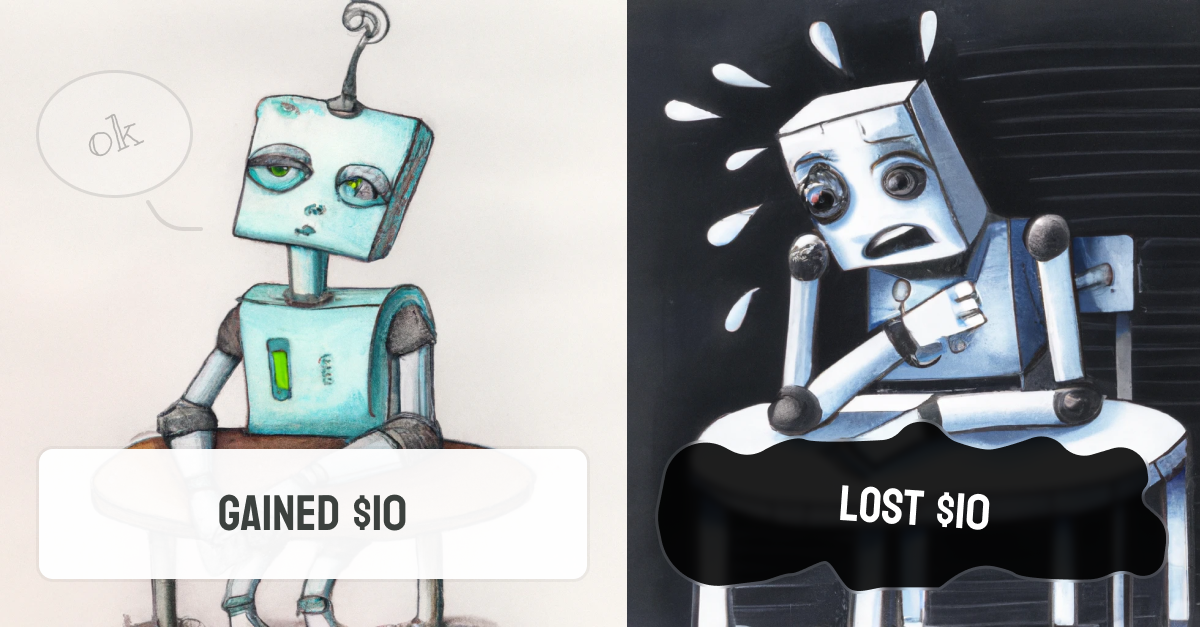

Pain is twice as worse as gain: why losses hurt so much

The cognitive bias known as loss aversion states that losses hurt relatively twice as much as equivalent gains. Here's why that matters to your wallet.

You arrive at your favorite casino and are immediately presented a choice:

Would you play a game in which you have a 50% chance of losing $100 and a 50% chance of winning $150?

Don’t worry if it took a moment to respond. The question has an emotional quality that merits a moment of reflection. While winning $150 sounds like a great start to a night, do you really want to risk kicking off an evening with such a loss?

Even if this gamble was presented at the end of the night—and even if you had a particularly good night on the casino floor—chances are you still paused to mull it over. And, if you’re like most people, the risk likely outweighed the reward.

Now what if the reward was $15,000 while the risk remained the same?

You probably didn’t have to think about that question for long.

Don’t lose at all costs

The cognitive bias known as loss aversion states that losses hurt relatively twice as much as equivalent gains. (Research shows it’s somewhere between 1.5 to 2.5 times higher; for some people, winning $150 in the above game is worth the gamble.)

The concept of loss aversion began to take form when Daniel Kahneman and Amos Tversky were contemplating utility theory—the idea that the utility of a gain can be assessed when comparing two states of wealth. Effectively, distinguishing between a gain or loss of $100 shouldn’t really matter. Winning that amount of money psychologically (and emotionally) should, according to traditional economic theory, register on the same level as losing that dollar figure.

Behavioral economics is the study of how humans actually act in the world, which, as these two researchers have repeatedly shown, is often irrational. Humans don’t act like characters in econ textbooks. And so they started approaching the question of utility differently.

This is how they initially framed the problem. To play along, choose one:

- Get $900 for sure or 90% chance to get $1,000

- Lose $900 for sure or 90% chance to lose $1,000

Framed this way, most people prove more conservative and take the sure $900 in the first construction. Yet even a 10% chance of not losing an additional $100 inspires most people to gamble in the second. This question helped form prospect theory, which became the basis of one of Kahneman and Tversky’s most famous papers.

Prospect theory led to the development of loss aversion, which basically states that we’ll feel roughly twice as bad about a loss as we’ll feel good about an equivalent gain. As they phrased it, “losses loom larger than gains.”

Think fast, and slow

In his book, Thinking, Fast and Slow, Kahneman writes that this cognitive bias has an important evolutionary utility. People who paid more attention to potential losses than potential gains were more likely to take fewer risks, thus passing along their genes. By contrast, risk takers are more likely to pay for their actions.

Of course, some people still love risk. Kahneman frames it this way: let’s pretend the opening gamble was a 50/50 chance of losing $100, but with three reward options.

- If you’re willing to win less than $100, you’re a risk seeker

- If you’re willing to win $100, you’re indifferent to risk

- If you’ll only play if you can win more than $100, you’re risk averse

Most people are risk averse. Somewhere between $150 and $250 is necessary for them to take the gamble.

Yet framing matters. As Kahneman and his associate, Richard Thaler, have both expressed, relative values are important.

For example, people are more likely to drive a few miles to another store if they discover they can save $10 on a $50 item, but less likely to hop in their car to save $10 on a $500 item.

Likewise, the difference between $100 and $200 is far greater in our imagination than the distance between $900 and $1,000, even though in both cases the difference is $100.

Interestingly, Kahneman writes that prospect theory and loss aversion are generally left out of textbooks. And he doesn’t mind.

There are good reasons for keeping prospect theory out of introductory texts. The basic concepts of economics are essentially intellectual tools, which are not easy to grasp even with the simplified and unrealistic assumptions about the nature of economic agents who interact in markets.

Questioning these mental models, he continues, could be damaging to those just grasping heady concepts for the first time. He’d rather students be empowered with the tools they need to navigate the imagined terrain before venturing out into the real world.

Yet we live in the real world, and humans are irrational with our money. In this case, a conservative bent is not necessarily a bad cognitive feature. It’s served us well in the past, and not everyone has the stomach for risk.

Knowing your tolerance, however, is important for managing your finances. Risks can pay off, but they can also do the opposite–quickly. For most, loss aversion is a north star that keeps them safe.